Tramonti is undoubtedly one of the best quality vine producer in the world. Did you know that it is also one of few places in the world that avoided the attack of Phylloxera, an insect that in 19th century led to the collapse of the wine industry?

Quality was always the most important thing for the wine producers from all over the world. That’s why for hundreds of years winegrowers tried to select only those wine grape varieties that were giving the best quality fruits. The price that had to be paid for the high quality of the product was the enormous sensitivity of the grapevine to the diseases. How high this price would be the farmers were to learn in the second half of the 19th century, with the arrival to Europe an inconspicuous visitor from America (at least at the first sight) the phylloxera.

PHYLLOXERA BECOMES A WROLD TRAVELLER

But how did this small aphid appear on the Old Continent after all? With the help of man, of course. Eurpoean winegrowers began to import grapevine seedlings from America; seedlings in which phylloxera lived. In the past, the poor thing had never managed to reach Europe, it would die before the ship could get to the port. But the situation changed drastically with the take-up of steamboats. The three-week journey was no longer lethal for phylloxera. It arrived to Europe and, unfortunately for all wine producers, liked it there very much.

THE FIRST STRIKE

It all began in France. Phylloxera attacked for the first time near Avignon, in 1863. A new disease that was causing the withering of leaves appeared. Two years later, farmers noticed that some infected plants began to die. By the end of 1867 phylloxera, operating undercover, completely destroyed few large vineyards near the Lower Rhone.

THE INQUIRY

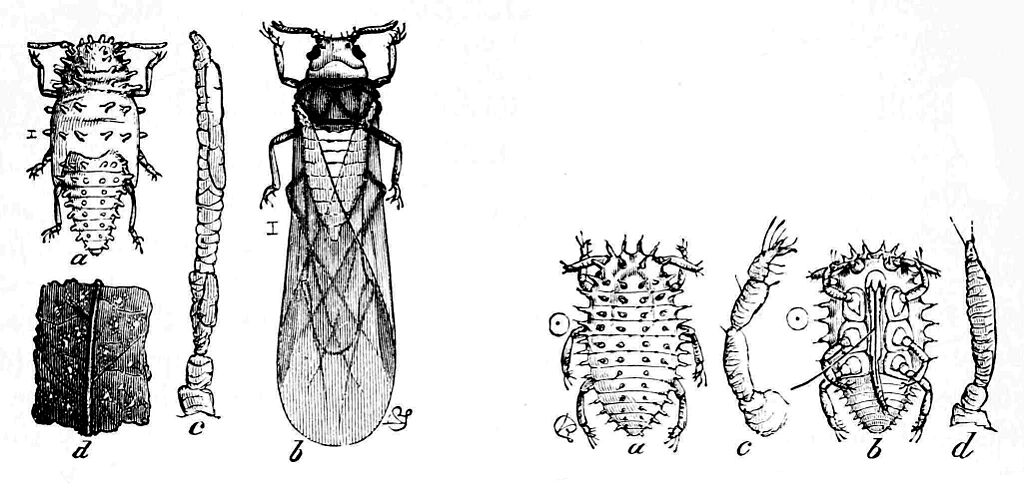

Concerned farmers turned to the Société Centrale d’Agricolture de l’Hérault (very esteemed at the time argicultural society) with a request to investigate the matter. A three-man committee initially focused on the study of dead grapevines. They didn’t find anything suspect so decided to dig up sick, but still alive plant. That was when they discovered that the roots were covered with a yellow coating. After looking through the magnifying glass, it turned out that the yellow spots were in fact colonies of microscopic insects. It was named phylloxera vastatrix (because of the resemblance to phylloxera quercus, an insect that was attacking the oak leaves). Further research had shown that phylloxera vastatrix was in fact the same species that was attacking leaves in American vineyards and that it could very quickly reproduce on the roots of healthy European grapevines.

PANDEMIC

In 1870, the insect appeared in virtually every vineyard in France. Soon after, phylloxera “wandered” into Portugal, Turkey, Austria, Germany, Hungary and Switzerland. In 1875, it attacked also Italian vineyards. After 1880, basically all European vineyards, from the Balkans to Russia, were infected. The plague reached even Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

THE REMEDY

After many studies, it turned out that “the root form” of phylloxera did not attack the roots of some American grapevines. Thus, traditional varieties of European grapes were grafted onto stocks of their American cousins. A large-scale replanting of the vast areas of destroyed vineyards has begun. The nightmare ended and viticulture in Europe has been saved. But before that happened, the phylloxera had changed forever the wine map of the world. The wine industry was on the verge of collapse. In 1888, 68 thousand hectares of vineyards were destroyed in France alone! Hungary, which before the attack of phylloxera was the second wine producer in the world, at the late 19th century had to import it to satisfy their own needs.

HOW DID TRAMONTI SURVIVE?

Also in Italy, several tens of percent of the vineyards were destroyed and entire towns in the south of the country were almost completely depopulated. Fortunately, there are areas that phylloxera didn’t reach. One of them is Tramonti. How did it happen that this area survived? The volcanic soil turned out to be a savior. The baby Phylloxera (larva) couldn’t move in the non-homogeneous, humus-deprived environment. The aphid, for its part, didn’t like windy climate. Therefore, today, Tramonti is one of the few places in the world where you can see a 500-year-old grapevine, which happily avoided the attack of a murderous insect.